The fear factor: Why Singaporeans dread retirement

Financial adviser Patrick Chang, 58, is championing a different kind of retirement.

He has written a self-published book about retirement, The A To Z Guide To Retirement Planning: Everything You Need To Know About Accumulating And Preserving Wealth For Your Golden Years (2016). He is now working on his second book, Retire Retirement, Welcome Protirement: The Essentials A To Z.

He is an advocate of protirement, a term coined in the early 1960s, defined as retirement from professional work in order to pursue something more fulfilling. A good protirement can encompass a new career or hobby that draws on one's years of experience and expertise. Older people are encouraged to pursue their interests and mentor younger workers, sharing their skills and wisdom.

Mr Chang says: "In my interpretation, protirement is proactive retirement. Instead of stopping work altogether, waiting to reach the traditional retirement age, or being forced to retire due to circumstances, individuals in protirement actively plan and design a lifestyle that balances work, leisure and personal growth."

This could take the form of passion projects, consultancy, freelance or part-time work, volunteering, fitness goals and lifelong learning, he says.

He got the idea for his second book on retirement while conducting anti-scam training workshops for seniors in recent years. The seniors, he recalls, were raring to share their knowledge, keep working and explore different interests, but they were unsure how to.

Mr Chang is preparing for his own protirement. He has been investing for his and his wife's retirement needs for about 10 years. He is married to a 52-year-old executive at a freight forwarding firm and the couple have 16-year-old twins.

Having gained qualifications in life and career coaching, he aims to be certified in corporate team coaching soon. Now working in a financial advisory firm, he plans to run his own coaching business after he retires.

"Protirement is about having the agency to shape a new life beyond retirement. I'm looking forward to it with excitement," he says.

He is among 25 working Singaporeans aged 35 to 75 across diverse socio-economic backgrounds and ethnicities whom The Straits Times interviewed about their attitudes towards retirement. These included a part-time blue-collar employee earning $800 a month, a cleaner, a security services manager, as well as a law firm partner who makes about $2 million a year.

Delving into the psychology of retirement planning, the interviews sought to find out their state of mind regarding retirement.

The range of emotions ran the gamut from worry to indifference to optimism about stopping work for good. A consistent theme was the desire to maintain good health and autonomy as the interviewees were aware that high medical costs or illness could upend retirement plans.

One communications manager went on a "trial retirement" in her 50s and decided she never wants to stop work. A sales assistant, in her 60s, has a carefree approach towards life and plans to rely on her children in her old age. Mindful of the rising costs of living, a 35-year-old businessman has made plans to move to Indonesia, where he hopes to retire at 45.

Fear of retirement

A common thread in the interviews was a fear of retirement, which experts say can result in inertia surrounding retirement planning, which has larger implications for Singapore.

Luqman (not his real name), a 52-year-old operations technician, is fearful about losing his financial independence if he stops work.

The married father of four children says: "I don't plan to retire; I don't want to. Retirement is a frightening term. Societal factors like the rising cost of living contribute to this fear."

"I don't want to be a burden to my children when I am older," he adds, saying that he sees it as his duty to finance his children's education, which he has done by investing in insurance policies over the years.

He does not plan to remain in his job after retirement age and hopes to "stay active" by running a small food and beverage business with his wife, a white-collar professional.

He attributes his negative view of retirement to witnessing family members dying of illness shortly after they stopped work and not getting the chance to enjoy their golden years.

Singapore's current retirement age of 63 will be raised to 64 on July 1, 2026. The re-employment age will likewise go up, from 68 to 69. Companies must offer eligible staff re-employment until that age, on amended terms if necessary, or offer employment assistance instead.

The Government has said the retirement age will be increased to 65 and the re-employment age to 70 by the year 2030.

Singapore is poised to become a "super-aged" society. By 2030, one in four citizens - or 25 per cent - will be aged 65 and above. The United Nations defines a country as "ageing" if the proportion of its population aged 65 and above crosses 7 per cent. It is "aged" if this proportion exceeds 14 per cent, and "super-aged" when it reaches 21 per cent.

A zest for work

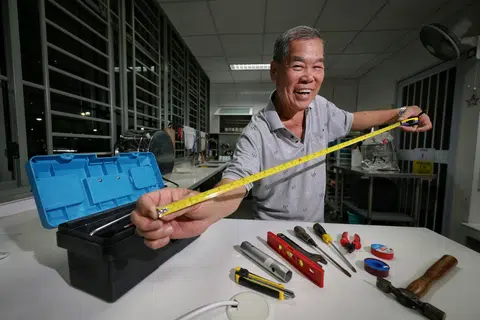

A desire to stay in the workforce for as long as possible was common among interviewees. Mr Fong Kok Wah, a 75-year-old supervisor of a team of repairmen at an industrial and facilities cleaning company, has a zeal for work long past retirement age.

Since starting his career in steelwork at 13, when he learnt to make window frames, he has moved from working with cranes and other heavy machinery to lighter work in his 60s, such as fixing pipes and general repairs.

He does this now in his free time at the Allkin Active Ageing Centre @ Punggol 677B in his neighbourhood, where he and his spouse, a 74-year-old housewife, are members. The couple have two children and four grandchildren.

Mr Fong says: "I have been working for so long and I will have to find activities to fill my time when I retire. I have no concerns about retirement, save one. If I fall ill, medical fees will be a big burden."

He reckons he will have to retire from his current job in two years' time at age 77 when the certificate of entitlement runs out on his motorcycle, which he rides to work at Jurong Island. He already has his eye on a different kind of work: transporting patients in wheelchairs to medical appointments as a healthcare porter.

Meanwhile, veteran food retailer Abdul Latip Isnin, 68, has few financial worries, but misses the "adrenaline" of work.

After running about 200 supermarkets in Indonesia at his peak in the early 2000s, he was forced by Covid-19 to take a break from 2020 to 2022 when social distancing and global travel limitations took effect. At age 63, he scaled back and did freelance consultancy work in food retail.

When the managing director position at HSG Global, which imports, exports and distributes halal food, was offered to him in 2023, he leapt at it.

"There was a vacuum in my life when Covid-19 hit, and I stopped full-time work. I found I needed to do a lot more to keep myself busy. Work helps me continue to be healthy and mentally well," says Mr Latip, who is married to a housewife with an adult daughter. He is also a board member at the Singapore Malay Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

He thinks he will call it a day eventually at age 72 if his health bears up.

"You have to be realistic. Somewhere along the line, you have to retire. On top of CPF, which gives one security, one has to have another source of income such as passive income from a rental property."

Others, like Sharon (not her real name), 53, staged a "trial retirement" three years ago, found it disastrous and backpedalled to work.

Then working in sales and fed up with her demanding schedule, she quit at age 50. But she felt "lost" during her six months away from work despite being financially secure and packing her days with coding and pottery courses, pilates and volunteering, as well as spending more time with loved ones.

"By the second month, I realised I had too much time on my hands. I will not think about retirement any more because I can't sit still. There will always be a way for me to find a job," says Sharon, who is now back to full-time work as a communications manager.

Anxiety over inflation

The pandemic, which saw housing rents surge, marked the start of anxiety about retirement planning for Ms Yang Xiao, 40.

In 2022, her landlord asked for an 80 per cent increase on the rent on her family's condominium in the Balmoral area, compared with what she paid two years prior, she says, declining to give specific figures.

"That was when I started worrying about our retirement future, about inflation. I had never worried about affording rent before," says Ms Xiao, who runs a social media marketing firm, Xiao Saunders Consultation. The Singapore citizen is married to a British telecommunications analyst, and they have two children, aged 13 and nine.

While she plans actively for retirement by topping up her Central Provident Fund and investing, trying to outstrip inflation is stressful.

"I'm proactively learning and talking to as many advisers as possible, but the speed of my learning is too slow. What adds to my anxiety is that my income varies from month to month," she says.

Meanwhile, Zain (not his real name), a 35-year-old who runs fitness and interior design businesses, has taken steps to move overseas for the kind of early retirement he aspires to.

"I'm in the process of migrating for retirement because the cost of living is high here. Being in Singapore, I can't have peace of mind," he says.

He has applied for a visa to work on the island of Bali, where he hopes to open a cafe and retire by the age of 45.

A sense of freedom

For others, however, the R word evokes a sense of liberty and ease, or at least, a stoic acceptance.

Adam (not his real name) has been planning for retirement all his life, from when he started work in his early 20s and set aside at least $100 a month in savings.

The law firm partner in his 50s estimates he earns between $1.8 million and $2.5 million a year. He aims to retire in five years with a diversified portfolio, including property and investments, that will continue to generate income for him.

"I know I come from a position of tremendous privilege to be able to do this. It's harder for younger lawyers to make partner these days. It allows me to look forward to retirement with anticipation and to be generous with the people around me," he says.

"I always had financial insecurity when I was young. While I cannot predict health matters or people not being around one day, what I can hopefully control is financial security. Money is one of the biggest sources of worry and this allows me to truly have freedom," he adds.

He imagines retirement being filled with languid meals with friends and family, sleeping in till noon, travel, reading and volunteer work with seniors.

In contrast, June (not her real name), 67, feels there is "no need to think or plan" for retirement. She and her security guard husband have paid the mortgage on their HDB flat and raised two children. They have three grandchildren now.

The part-time saleswoman says: "I can retire any time, there's no need to worry. I feel happy and my money is enough. Our children don't need to worry about us, that's so important."

When friends discuss the rising cost of living, she does not weigh in, she says, adding she has few expenses now.

While she confesses she probably needs more information about financial planning for retirement, she says: "I don't go and find out. Maybe it's because I am still healthy. If I am not healthy, maybe I will need that information. It's not urgent because our children will plan for us if we're old and in ill health."

Meanwhile, Ah Ming (not his real name) is phlegmatic about imminent retirement. "No choice," says the 71-year-old bachelor, who works part-time in a factory.

He collects a monthly CPF Lifelong Income for the Elderly (CPF Life) payout of less than $900 and earns $800 a month. CDC vouchers and other government disbursements help him cope with rising costs, and he receives monthly donations of rice, sugar, garlic and other sundries from a charity.

In recent years, he downsized from a three-room HDB flat to a two-room one, and used funds from the sale to prepare for retirement. He exercises twice a week to maintain his health.

He adds: "I don't want to depend on others. I have enough to retire on. The Government should help those who are poorer."

How much is enough?

Why does the perception of what is enough to retire on differ so much?

Explaining why some higher-earning individuals may be more anxious about retirement than others on much lower wages, psychology professor Andy Ho says: "Higher earners may be more financially savvy about costs of living, expenditure and investments, while others earning lower incomes may have no viable agency (in being able to spend more) - they may need to rely on tradition and cultural norms, such as filial piety from their children in old age.

"It is important to note that individuals on lower wages do feel anxious about retirement planning, but they are fully absorbed with simply putting food on the table and making ends meet every month. These conditions may render retirement planning unfeasible and not a major life priority."

Prof Ho, who is the provost's chair professor of psychology at Nanyang Technological University, adds: "High-income earners may also want to maintain the high standard of living they are used to, as much as possible."

What is clear across the board, say experts, is that awareness of Singapore's "super-aged" status has permeated society, raising questions about what retirement means, not only in terms of one's finances, but also its purpose and one's identity apart from work.

Associate Professor Thang Leng Leng, an anthropologist at the Department of Japanese Studies at National University of Singapore, says: "We hear so much on the news about how Singapore has one of the highest life expectancies in the world.

"This narrative about a possible 100-year life gets people thinking: How am I going to have a meaningful life if I live to my 90s? Will I have enough money? What happens with work?"

"Rising costs of living also make people aware that if they retire, they may not have enough to have the kind of lifestyle they want."

To be sure, work imparts a sense of identity, especially for men, she observes, and leaving paid work can impact one's mental and physical health and social well-being.

She adds: "Maybe individuals have to better define what retirement planning is for themselves. They should think about what is important to them in order to live happily and comfortably in old age."

Dr Kelvin Tan, a senior lecturer in gerontology at Singapore University of Social Sciences, says that "trust in the Government is high" when it comes to ageing issues.

Social phenomena in Singapore - such as the acceptance of flexible work arrangements, a pro-work culture, a perception of the value of CPF as a "sound system" and ageing-friendly HDB accommodation - also provide support and a sense of having choices in retired life, he adds.

But experts say active retirement planning should be more widely encouraged instead of feared and avoided.

Prof Ho notes that there are typical responses to major life changes, which factor in motivating people to think about key life stages like retirement.

"When faced with major life changes, people tend to either procrastinate, trivialise the event or accept and face it head on, often when it is imminent. Social comparison is important. How imminently they view the change depends on whether they personally see others in their lives facing similar challenges, which may lead them to think: 'Hey, I have to deal with this.'"

To motivate Singaporeans to address big changes like retirement or end-of-life issues on a societal level, "we need the entire system to work towards this goal", he says. This includes the financial industry, the insurers, the Government and other stakeholders, he adds.

"Singapore is going to be a super-aged society. The sooner we start thinking about retirement planning, the more prepared we will be and the easier the transition will become," he says.

If that happens, at least more Singaporeans will be like Mr Chang, filled with hope, not dread, about the end of paid work, and buzzing with plans for new beginnings.

Venessa Lee for The Straits Times