Nearly all unagi in S'pore from endangered eel species: Study

Pick out an unagi dish at a local restaurant or supermarket, and chances are it contains an endangered eel.

This was what a team of scientists from Yale-NUS College recently discovered, after analysing 257 unagi products, including dried, cooked and fresh meat, from various stores in Singapore.

They found that 99.6 per cent of the products contained genetic traces of threatened freshwater eel species. They published their research on Jan 9, in the journal Conservation Science And Practice.

Unagi is the Japanese word for freshwater eels, which are often consumed in East Asia as a grilled and glazed delicacy. High consumer demand for these eels, which belong to the family Anguillidae, have resulted in their being overfished.

There are about 19 species of freshwater eels worldwide, although it is mainly three species that are consumed in Singapore.

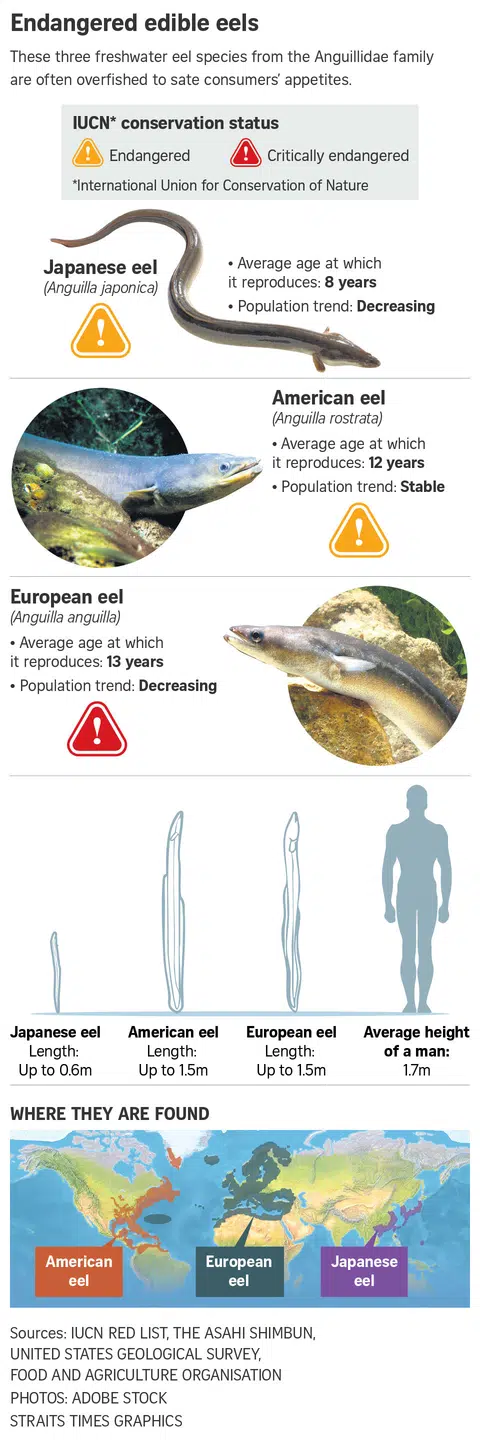

They include the Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica), European eel (Anguilla anguilla) and American eel (Anguilla rostrata), said the study's principal investigator, Mr Joshua Choo.

The European eel is critically endangered, while the other two species are endangered, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List, which outlines the conservation status of animals, plants and fungi.

Despite the European Union's establishment of a zero-export quota on the European eel in 2011, Mr Choo's team came across a 2020 report showing a high prevalence of the eel in Hong Kong's stores.

This prompted them to investigate if this trend holds true in Singapore.

For the study, Mr Choo - a Yale-NUS environmental studies undergraduate at the time of the research - and his team collected 266 freshwater eel meat samples from retailers and online shops that ship products to Singapore in July 2023.

They bought a range of dried, cooked and fresh meat to ensure diversity.

The researchers then identified the species of eel in each product by extracting its DNA and comparing it against known genetic sequences of different eel species.

But instead of European eels, the researchers found that a large proportion of eels sold in stores here were American eels.

Among the 257 unagi products for which DNA was obtained, 217 (84.4 per cent) were identified as the American eel.

Another 36 samples (14 per cent) were of the Japanese eel, while only three samples were found to contain the European eel.

One sample turned out to be the pink cusk-eel, a saltwater species which had been incorrectly labelled as unagi.

According to Mr Choo, this signals a worrying shift - towards the American eel as a substitute for already depleted European eel stocks. He added that this cycle of exploitation, depletion, and moving on to another species is well-documented in the eel trade.

The Japanese eel had been the first target species for unagi dishes, but its overconsumption led to population decline, and consequently a rise in its cost.

European eel was comparably more cheaply priced, so the industry turned to this species instead. According to a report by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (Cites), from the late 1990s to 2007, more than 50 per cent of exported juvenile European eels landed in aquaculture farms in Asia.

But now that population numbers of the European eel are plummeting too, industry preferences are shifting once again to the American eel populations.

Citing a different study, Mr Choo said: "East Asia has been importing more and more American eels - from two tonnes in 2004, to 53 tonnes in 2021 and 157 tonnes in 2022."

And researchers now fear that freshwater eels in South-east Asia could be the next target.

Most eels that are served as unagi are wild-caught as juveniles as they are difficult to rear in captivity due to their complex life cycle.

Mr Choo said young eels hatch in the open ocean, and swim to freshwater, where they mature into "glass eels", as they are known in this stage of their life cycle.

Subsequently, they change into elvers, yellow eels, then silver eels - sexually mature adults - that return to the open ocean to mate and spawn.

He said: "The eels only mature and breed after encountering certain environmental conditions during migration - a journey that is hard to simulate in captivity."

The youngest eels, known as leptocephali, also often die in captivity, Mr Choo said. They feed on marine snow - biological debris originating at the top of the ocean, such as the faeces or decaying carcasses of other fish - which is difficult to replicate in aquaculture.

Farmers have thus turned to using wild-caught glass eels as broodstock, and raising them till they grow into yellow and silver eels - which are then sold to retailers. As with silver eels, yellow eels - which are the immature adult stage of eels - are also seen as a delicacy by consumers.

As many are siphoned to aquaculture farms, fewer juvenile eels reach maturity in the wild, resulting in inadequate replacement rates.

The fishing pressure on these eels is exacerbated by their high value, and the ease of smuggling them, especially as juveniles.

According to Europol's estimates, the illegal glass eel trade rakes in profits of "up to €3 billion (S$4.36 billion) in peak years" - more than that of the illegal arms trade, which generates between €125 million to €236 million each year, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Trafficked glass eels are also translucent and small, growing up to only 7cm in length. This makes them difficult to detect, and allows a large quantity of them to be transported at once.

Mr Choo said: "They look like a pile of T-shirts under the X-ray machine, so it's hard to catch that they're being smuggled."

Aside from fishing pressures, freshwater eels' migration to the ocean may also be impeded by other factors, such as the construction of hydroelectric dams, and changing ocean currents attributed to climate change.

As consumers, Mr Choo suggested reducing the consumption of eel meat, or completely eliminating the fish from one's diet.

Local eel retailers have a role to play as well, said Mr Chester Gan, senior manager of conservation for oceans and nature-based solutions at the World Wide Fund for Nature Singapore.

He said: "Making responsible food choices can be challenging for consumers when eel products lack clear labelling - often missing key details like species, origin and production methods.

"But by adopting clearer labelling and ensuring greater transparency in sourcing, they can empower consumers to make informed choices."

Mr Choo also emphasised a need for stronger transboundary cooperation, including efforts to list more endangered eel species on the Cites agreement - a multilateral treaty to safeguard threatened species from international trade.

Currently, only the European eels are listed on Cites.

Other researchers, such as Dr Tan Heok Hui, a fish scientist at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, have echoed this sentiment.

He said: "For the eel trade, more efforts need to be invested into identifying the eels in our stores, and conducting timely re-assessments of their stock and threat levels in the wild."

Mr Choo also said that more research is needed on other eel species, especially understudied tropical anguillid eels like the Celebes longfin eel (Anguilla celebesensis), which is native to some regions in South-east Asia, such as Indonesia and the Philippines.

He said: "The eel trade could expand its reach to include regional relatives to the American and European eel - which are found in places like Malaysia and the Philippines. But yet there's still a lot that is unknown about them - some are even data deficient because we just don't have people studying them."

Despite current trends, the researcher remains optimistic that there is hope for our threatened freshwater eels.

He said: "I do think the populations can bounce back, but it will take time, and the decision to prioritise reciprocity over profit as a society."

Angelica Ang for The Straits Times