University fees: A parental obligation or a student's burden?

This long-standing question has sparked many debates over the years.

For older generations, the answer was often clearer: tertiary education fees were typically paid by students, especially when pursuing university studies was less common.

However, with rising incomes and the perceived necessity of a university degree in today's society, the question of who foots the bill has gained prominence.

A recent Reddit post highlighted a startling reality for some. The user, a student accepted into medical school at both the National University of Singapore (NUS) and Nanyang Technological University (NTU), expressed exasperation over their parents' refusal to fund their university degree.

To compound the issue, the student's parents also expected financial support from their children upon retirement.

While such situations may not be the norm for many Singaporean families, this case raises a pertinent question: beyond mandatory education, are parents responsible for funding their child's tertiary studies, or should young adults bear the cost themselves?

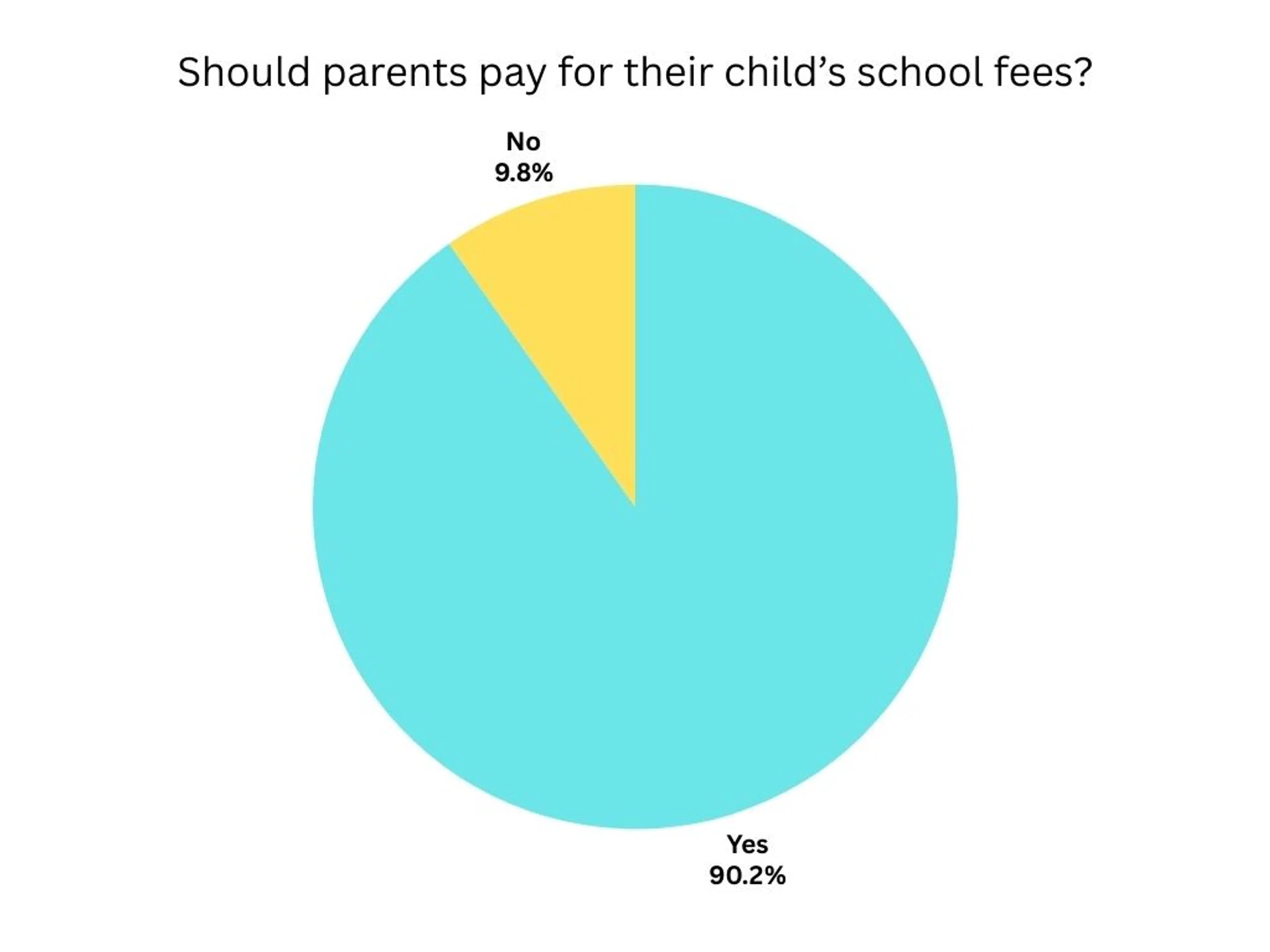

The New Paper surveyed 60 students, aged 16 to 25, from various institutes of higher learning, including Junior Colleges, Polytechnics, the Institute of Technical Education (ITE), and Universities.

A significant 90.2 per cent of students surveyed believe funding a child's tertiary education is an inherent parental responsibility, viewing it more as a right than something to be earned.

A 19-year-old polytechnic student commented: "I think it's unfair not to pay. When bringing kids into the world, parents have the responsibility to raise them in a safe manner, both mentally and physically. Refusing to pay [for higher education] is not ensuring a good and safe environment for children."

Some respondents suggested that if parents are unable to fund their child's education, it could indicate poor family planning, thereby creating unnecessary stress for the child.

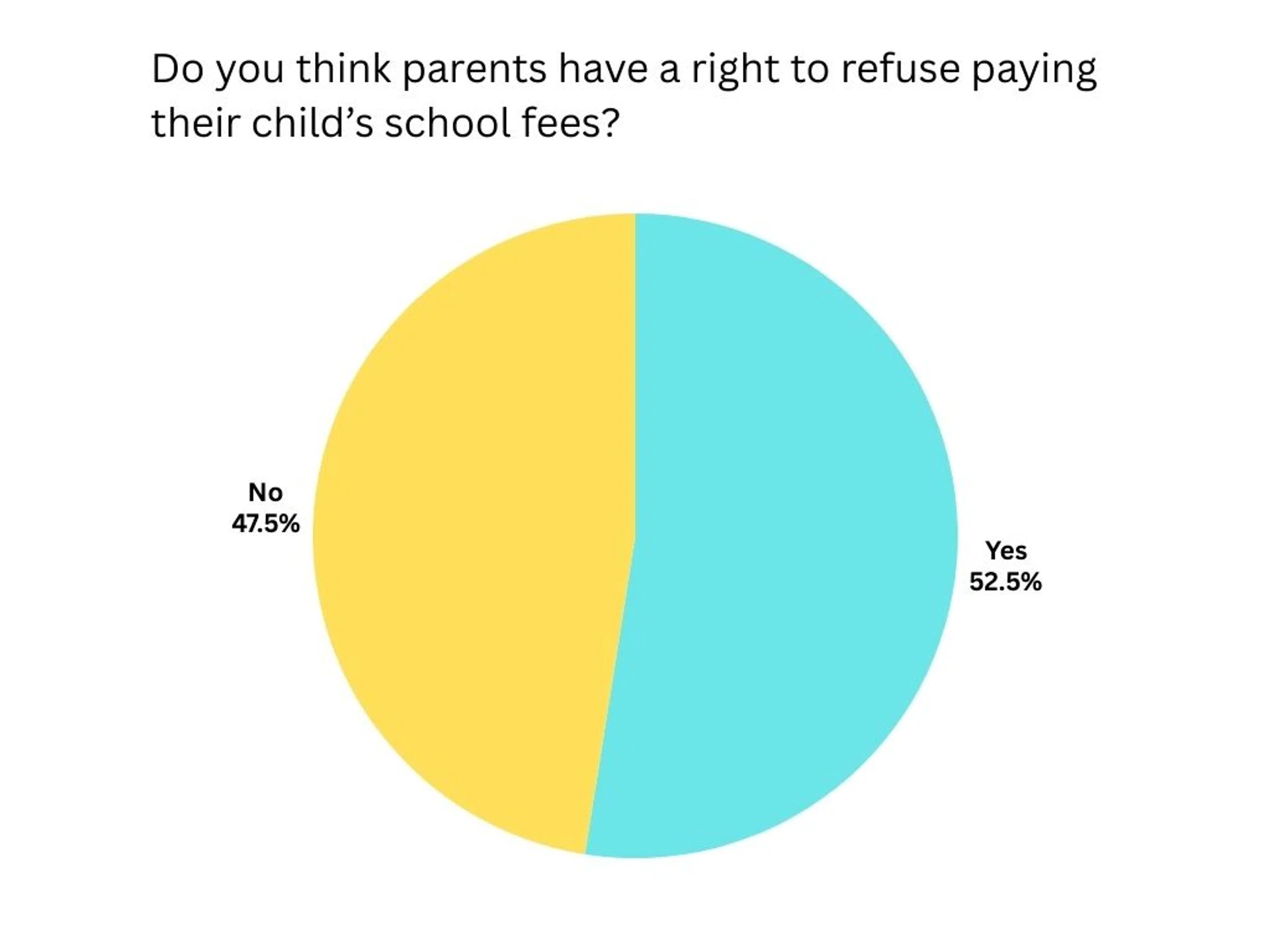

However, 52.5 per cent of respondents also believed parents have the right to refuse to pay their children's school fees.

They reasoned that valid circumstances might exist, such as a desire to teach independence.

One university student remarked: "It depends on their circumstances and their belief system; they might feel that their child should learn independence and stop relying so much on their parents."

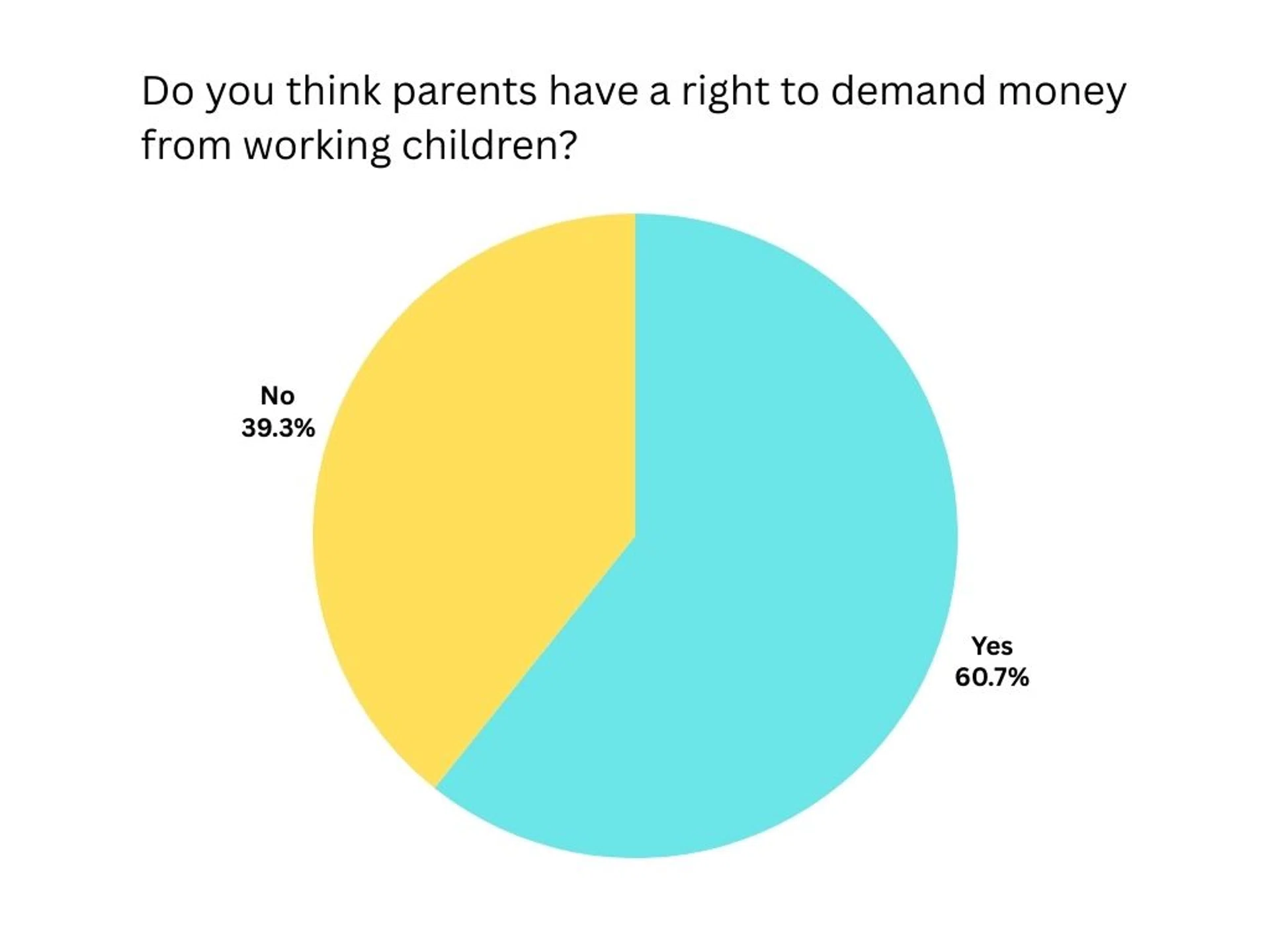

Students also had varying responses when asked whether parents have the right to demand money from their children.

Most acknowledged that, within the context of Asian culture where filial piety is emphasised, it is reasonable for parents to seek financial support from their children upon retirement.

A 20-year-old university student said: "It only seems fair, given our society's values of filial piety. Children should also develop the habit of setting money aside to support their parents, especially after their parents retire."

Reciprocity appears to be a key driver: students felt that if parents had supported them financially throughout their schooling, it is natural for children to give back when they are able.

Mr Ignatius Gan, a 21-year-old university student, suggested that financial support for parents should stem from gratitude: "Asking for money from your child should be a healthy, two-way interaction. The parents ask, and the child is happy to give."

However, other respondents felt that when financial support becomes an expectation or demand, it crosses a line.

"It no longer makes it okay, especially if your parents expect you to 'return' the money they spent raising you. Then why have kids if they're just bank investments to you?" said Miss Genevieve Tan, 21.

Ultimately, many students believe that once an adult child begins earning their own income, they should decide how to spend it.

Currently, the Maintenance of Parents Act in Singapore allows parents aged 60 and older, who are unable to support themselves, to claim financial maintenance from children who have the means to provide it.

However, a key point of contention, as some see it, is that while the Act enforces an obligation, true willingness to provide support often stems from reciprocity. Children may feel more inclined to support parents if they themselves felt supported throughout their childhood. Strained parent-child relationships can complicate this, as support given purely to avoid a lawsuit may not resolve underlying issues.

Perhaps the focus should be on mending estranged family relationships and tackling the root of emotional disconnects, rather than relying solely on legal mechanisms. Laws like the Maintenance of Parents Act provide a safety net, but they cannot legislate love, trust or mutual care.

In a society where both independence and interdependence are increasingly valued, the conversation around who pays - and who gives back - will continue to evolve.

If there is one takeaway, it is that financial responsibility within families is rarely just about money. It often involves the invisible emotional debts accumulated over time, and how each generation chooses to settle them.